By Heather Blumenthal

For people with cancer, COVID-19 poses a triple threat. First, their immune systems are suppressed, due both to the simple fact of having cancer, but also potentially as a result of cancer treatment, making them more vulnerable to severe illness should they be infected with the virus. Second, it’s hard to isolate – a key tool in preventing infection – when you’re undergoing cancer treatment, because of frequent, even daily, visits to the hospital. And third, even though there has been good news in recent days about vaccines against COVID-19, there’s no indication yet of whether these vaccines will be effective in people with cancer.

This trifecta of bad news got Rebecca Auer thinking about how cancer patients could be protected against COVID-19. And the first thing that came to mind was BCG, a vaccine against tuberculosis.

Research has shown that, while it prevents the disease it targets, BCG also prevents other respiratory viruses. It is also been shown to improve responses to other vaccines, such as the flu shot. The only problem is, the vaccine is made with live bacteria, and although the bacteria is in a weakened form, it is still too risky to give to immunosuppressed cancer patients. So she started looking around for similar substances that used a killed version of the bacteria.

Dr. Auer, a Senior Scientist and Surgical Oncologist at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, also looked for inspiration in a more obscure place – the beef industry, where cattle are shipped long distances in crowded quarters. These cattle are vaccinated with an innate immune system booster to prevent many different types of respiratory infections, a strategy that has worked well. Even before COVID-19, Dr. Auer was exploring whether this strategy could be used before cancer surgery to boost the immune system, which could improve recovery and prevent the cancer from coming back. It was a short step to applying the same strategy to preventing COVID-19 – or for that matter, any viral infection – in these same patients.

What happened next was pretty much unprecedented in its speed and came together because of the joint efforts of a large cast of characters.

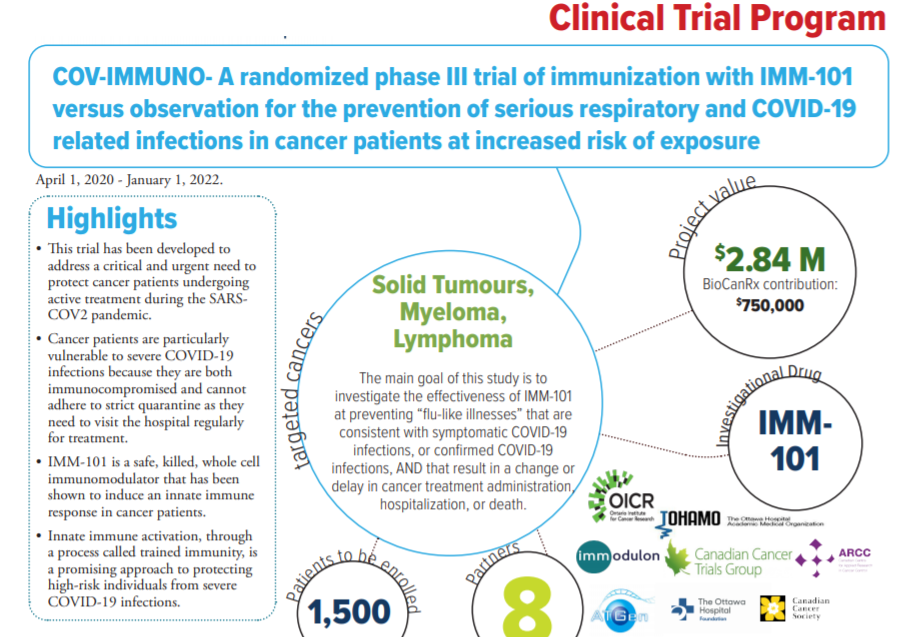

The first step was to find a company that already had an innate immune-system booster. That information came courtesy of Dr. Laszlo Radvanyi, President and Chief Scientific Officer of the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, who, Dr. Auer says, “knows lots of people and is good at making connections.” He pointed Dr. Auer toward a British company called Immodulon Therapeutics, which had developed and was already testing IMM-101, an innate immune system booster that used a heat-killed virus, as an adjunct to immunotherapy and chemotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer, melanoma and other types of cancer.

Dr. O’Callaghan was excited by the fact that IMM-101, first developed as a kind of immunotherapy, was already being tested in cancer patients. As a result, it’s already been demonstrated to be safe in this population; now, it’s a question of finding out whether it’s also effective at fighting COVID-19. Dr. O’Callaghan calls it being “opportunistic.”

From the end of March, when Dr. Auer first began considering the problem, things happened at lightning speed. In April and May, the group put together funding applications (including a successful application to BioCanRx) and developed the trial protocol. In June, the protocol was submitted to Health Canada and approved. By September, the trial was open, recruiting patients.

“This was definitely different from what everyone was used to,” says Dr. Auer.

Vaccine trials are different from regular drug trials, says Dr. O’Callaghan. With a drug trial, in simple terms, you give one group of patients the drug and another a placebo and you measure what happens. With vaccine trials, you give one group of people the vaccine and another a placebo – but then you wait. You wait until enough people get the virus so that you can assess whether the vaccine made a difference. So it’s hard to say how long this trial is going to take.

“We just have to watch it and wait.” He adds, however, that they are focusing on the hardest-hit cities across the country – Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver. Both he and Dr. Auer believe they could have results within about a year. They also believe that they are doing this trial at exactly the right time, as cases are rising with the second wave of infection.

So, if COVID-19 poses a triple threat to cancer patients, IMM-101 could provide a triple benefit: it could immunize patients against COVID-19; it could improve patients’ response to an eventual COVID-19 vaccine; and it could have benefits against other respiratory viruses. And, if that’s not enough, IMM-101 may also have anti-cancer properties. Now that’s something to celebrate, even in these distinctly uncelebratory times.

See project summary for more details

Heather Blumenthal has been writing about health and health research for more than 20 years and never loses her fascination with the advances Canadian researchers are making.